A Cantankerous Hanseatic Cartographer reads Juvenal

An eccentric study in Germanness and Latinitas though the lease of Juvenal's Second Satire

The Pro Iuvenale Apologeticus and Commentary by Eilhard Lubinus (1603) can be placed in a tradition dating back to late antiquity, in which Juvenal is celebrated as an auctor ethicus (ethical author). The present essay attempts to elucidate the various reasons why our dear Lubinus arrived at this view, as well as to clarify the methods by which he substantiates this perspective.

The Pro Iuvenale Apologeticus

“O saeculum, o litterae ... O Jahrhundert, o Wissenschaften, es ist eine Lust zu leben, wenn auch noch nicht, sich zur Ruhe zu setzen, Willibald. Es blühen die Studien, die Geister regen sich! Du, nimm den Strick, Barbarei, und mache Dich auf Verbannung gefasst!”1 With such glowing optimism writes Ulrich von Hutten (1488 - 1523) to his contemporary Willibald Pirckheimer (1470 - 1530) lauding the glories of their age. Some forty years later, Thomas Naogeorgus (1508 - 1563), with the pithy bitterness of a world-worn cynic, writes:

Quando etiam edendi quaevis tam prompta facultas?

Temporis exiguo tres exemplaria mille

Excudunt spacio, nihil et conscribitur usquam

Insulsum pravumque adeo vel inutile, quod non

Applausorem habeat, quod non mox gestiat autor

A parvis magnisque legi et dispergier orbe.When has there ever been such a ready means of publishing anything? In a brief span of time they print out three thousand copies, and nothing so dull, depraved, or useless is written anywhere that doesn't find someone to applaud it, that the author doesn't soon desire to be read by both small and great, and to be dispersed throughout the world.2

Less than half a century later, Eilhard Lubinus (1565 - 1621), far removed from the enthusiasm of a Hutten as well as the playful, ironic cynicism of a Naogeorgus, passes a damning judgment on his time in his Pro Iuvenale Apologeticus:

Cum autem omnia mundi tempora virtutum sterilia, vitiorum feracia maxime semper fuerint: Tum vero nullum agis deploratum, profligatum, impium, hoc, quo iam nos vivimus, nostro. Si enim umquam alio seculo opinio rationem, voluptas naturam, malitia virtutem, impietas DEVM profligare potuit et debuit, hoc nostro profligavit. Sane in quo inter innumera alia intolerabilia et indiqua primum est, quod cum omnia vitia et scelera passim inpunita sint, graviori pœna coerceatur, quam libere vitia reprehendere et veritatem dicere: Et de quo iustius illud proclamaverim, quod Iuvenalis de suo: Omne in præcipiti vitium stetit (Satyra 1.149).

While all ages of the world have always been barren of virtues and fertile in vices, none has been more deplorable, depraved, and impious than this one in which we now live. For if ever in any other age, opinion could and should have routed reason, pleasure nature, malice virtue, and impiety GOD, it has done so in our time. Indeed, among countless other intolerable and unworthy things, the foremost is that while all vices and crimes go unpunished everywhere, it is more severely punished to freely reprove vices and speak the truth: And of which I might more justly proclaim what Juvenal did of his own time: Every vice stands at the precipice (Satire 1.149).

Lubinus concludes this introductory invective with a paraphrase of Juvenal, which he applies concisely to his own time:

Verum enimvero cum illa in alios scribendi, et impune invehendi libertas in licentiam abitura hoc nostro sæculo, gravissimis de causis iniustissimis legibus et poena lege constituta sublata sit. Liceat saltem per importunos quosdam Aristarchos, et inepte religiosos priscorum monumenta in superioribus scholis, et illustribus Academiis legere, et in illis illud animadvertere, quod Iuvenalis de nobis vaticanitur, cum inquit: Eadem dicent facientque minores (Satyra 2.8) eandem nimirum Fabulam, quod dicunt, nostro etiam tempore agi, mutatis tantum personis.

But truly, since that freedom of writing about others and inveighing with impunity would turn into license in this our age, it has been abolished for very serious reasons by most unjust laws and punishment established by law. Let it at least be permitted, despite certain importunate Aristarchuses and ineptly religious persons, to read the monuments of the ancients in the higher schools and illustrious Academies, and to observe in them what Juvenal prophesies about us, when he says: ‘The younger generation will say and do the same things’ (Satire 2.8). Namely that the same Play, as they say, is being acted even in our time, with only the characters changed.

This is followed by a relatively brief biographical excursus on Juvenal, which on the one hand strives for a certain degree of objectivity (see remarks on Juvenal's relationship with Domitian, his exile to Egypt), but on the other hand serves Lubinus’ moralizing program. For example, Juvenal is said to have conducted legal proceedings until middle age and only then, “his indignation aroused by the abominable wickedness of the city of Rome,” devoted himself to poetry (Lubinus obviously and even somewhat dramatically aligns himself with Juvenal's pessimistic view).

Furthermore, he writes of Juvenal’s character: Porro vitae fuit sanctissimae et inculpatae et hostis scelerum acerrimus, de cuius praeclaro Satyrarum opere quid stauendum sit Fabius Q. indicat, cum tale de Satyricis lib. 10 fert iudicium (“Moreover, he lived a life of great holiness and blamelessness, being a fierce opponent of all vices. Regarding his renowned work of Satires, Quintilian offers guidance on what should be concluded, as he gives this judgment about the satirists in book 10”). The life of the author and the moral value of his work are linked, i.e., in his eyes, Juvenal must have possessed an almost flawless character, which confirms the moral-didactic value of his satire.

Juvenal the Stylist

Lubinus’ high esteem also applies to Juvenal’s eloquence as a stylist. Juvenal is described as a consummate poet, superior to Horace, himself superior to Lucilius. Lubinus quotes two passages from the Ars Poetica that have since become canonical (Ars Poetica, 333-4; 343) and asserts based on these: Non video cui unquam alteri inter Poetas, omnium recte intelligentium et iudicantium calculo rectius palma attribui possit, quam huic nostro (“I do not see to whom else among the Poets, by the calculation of all who rightly understand and judge, the palm could more rightly be attributed than to this our poet"). Hardly has he begun to praise Juvenal's stylistic perfection when he once again emphasizes his role as praeceptor morum (teacher of morals), this time with a very daring comparison between the Satires and the Nicomachean Ethics: Adeo ut adfirmare non verear in quibusdam Iuvenalis Satyris plus doctrinae, plus praeceptorum ad vitam et mores emandandos contineri, quam in integris decem Aristotles ad Nichomachum filium libris (“So that I do not hesitate to affirm that in some of Juvenal's Satires there is more doctrine, more precepts for correcting life and morals, than in all ten books of Aristotle to his son Nicomachus”). After this bold pronouncement, his status as a teacher is emphasized once more: Quis autem alius Ethnicorum Poetarum de Deo, et Divina Providentia, quae mundum gubernet, genus mortalium curet, probos cariores habeat, quam semel ipsos ipsi, malos iustis poenis adficiat, plenius et melius, addo et accuratius scripsit hoc Iuvenale [...] Iuvenalis te incredibli carminis dexteritate docebit (“What other pagan poet has written more fully and better, I add even more accurately, about God and Divine Providence, which governs the world, cares for the human race, holds the good dearer than they hold themselves, and afflicts the wicked with just punishments, than this Juvenal [...] Juvenal will teach you with incredible dexterity of verse”).

Juvenal’s Predecessors: Horace and Persius

Lubinus fully appreciates Horace, elevating his well-known maxim prodesse et delectare to the status of poetic ideal. There can be no doubt about Horace's position as a canonical poet, but in matters of satire, Lubinus argues that Horace is far inferior to Juvenal: Nisi Iuvenalis scripsisset, Horatio nemo esset melior (“If Juvenal had not written, no one would be better than Horace”). In stark contrast to Juvenal, who aperte [...] laccesit, invadit, flagellat, secat, urit, lacinat, iugulat (“openly attacks, invades, lashes, cuts, burns, mangles, and slays”), Horace wrote his Sermones quasi aliud agens ride[ns] (“as if doing something else, laughing”), in the spirit of ridendo dicere verum (“to speak the truth while laughing”), hoping that quicunque legat et intelligat, non possit non vitia maxime odisse et detestari et magno virtutis et honestatis ardore accendi (“whoever reads and understands them cannot help but hate vices and detest them, and be inflamed with a great zeal for virtue and honesty”). However, his Sermones are so stylistically refined and polished that one must ask whether he himself was a more useful (prodesse) or rather a more pleasant (delectare) poet. His often opaque language could make understanding difficult to such an extent that it leads more to boredom than enthusiasm. While Lubinus recognizes this limitation, he proffers a humorous anecdote — and not so subtle flex — that demonstrates the worth of Horace and of his own commentary: A certain Dietmar Wachmann, what we might nowadays call an “underprivileged” (damno denatum) student of Lubinus, would not send off his teacher on trip through Belgium until he had, to ease the tedium of the journey, explained all the Satires of Horace. Nonetheless, the linguistic difficulties in the Sermones might impair the average reader in appreciating the didactic function of the satire. With this in mind, Lubinus concludes: ex quibus omnibus hoc opinor [...] hunc Poetam reliquis omnibus non immerito omne punctum praeripuisse (“from all this I think [...] that this poet [Horace] has not undeservedly taken the lead from all the others”).

Persius

Unlike Horace, Persius does not receive any words of praise from Lubinus. He is said to insult indiscriminately with words that are difficult to understand and, as quoted from Scaliger, Persii stylus morosus et ille ineptus est (“Persius’ style is sullen and tasteless”).

Obscuritas and Obscœnitas

As a preface to the following section, Lubinus asks the question: Sic hoc Iuvenalis poema adeo eximium, adeo laudandum, quid fit quod hic auctor tam parum in manibus doctorum tritus? (“How can it be that such an excellent and praiseworthy work by Juvenal is so little handled by scholars?”). If Juvenal is accused of unclear language, this is, unlike in the case of Persius, more the fault of the unskilled scholar than of the author himself. Due to his sometimes obscene language, Juvenal—despite his outstanding achievement as a poet—was often discounted by scholars. Lubinus positions himself against those who feel morally repelled by this obscenity and intends to proceed differently: Quid aliis contigerit, quidem ignoro: ego sane, cum incredibiliem harum Satyrarum et doctrinam, et ingeniosam iucunditatem et elegantiam sentire occepi, tanta animi vehementia, et ardore ipsum legi, et perlustravi, ut omnes illas [...] cognoverim, et edidicerim, et etiamnunc memoria teneam (“What has happened to others, I do not know: I, for my part, when I began to feel the incredible learning, ingenious charm, and elegance of these Satires, read them and studied them with such great passion and enthusiasm that I came to know, learn, and even now remember them all”).

The Role of the Lubinus, the Commentator

Having established these ground rules, Lubinus explains his role as a commentator in mythologically charged language. Juvenal, long neglected due to barbarism, is likened to the dismembered Hippolytus, restored in his time by “Aesculapian” scholars through the “light of their knowledge”. His goal is to ex gripho scirpum redd[ere] (“to turn the riddle into a reed”). This task, however, will be successful only when Juvenal is no longer read by the youth as if he were a sphinx-like puzzle. After this brief explanation, Lubinus turns once more to the old commentators who avoided difficult passages “like sailors avoiding sea rocks.” Instead of fulfilling their duties as commentators, they focused more on outré words and did not dare to explain unclear or unlikely connections — and when they did indeed dare to venture this, they were too liberal in their On this basis, Lubinus makes the extravagant claim for himself: his commentary will explain everything down to the smallest detail so that after reading it, his students need not consult any other commentary. His work shall be a sacrifice upon the the altar of the dreaded German Ausführlichkeit (“thoroughness”) before which every student of classics recoils in fear and trembling.

After defining his role as a commentator, Lubinus — finally — addresses the contentious issue of obscenity. He anticipates the criticisms of those who will cry out that he has ventured into “the Scylla of obscenity”; the putatively vile material is contrasted, however, with his “crystal clear interpretation.” As mentioned earlier, Lubinus intends to proceed wholly different manner than his predecessors: whatever is in the text should be named and explained. Following Scaliger, he writes: Scapha, ut est in proverbio, scapha dicenda est (“A boat, as the proverb says, must be called a boat”). Those who prefer to censor Juvenal rather than explain him lack an understanding of the poet’s personality, for he was not guilty of sin but openly rebuked it. By their censorship, they exile the world and human affairs; they are arrogant and act out of a ficta pietate (“false piety”) born of their hypocrisy. Lubinus concludes with the question: iam vero quis, miram dicam an diram, quorundam sanctimoniam tulerit? (“Who can tolerate, I wonder, the strange or perhaps dreadful piety of certain people?”). To those who are offended by his coarse language, Lubinus gives a single piece of advice: At quorum tamen sanctissimae auriculae, si forsan huius Poetae obscoenitate offendantur, qui amplius aut melius remedium illis obtulerim, quam illud huius Poetae (Satyra 14.44-45)...: quid tamen expectant, Phrygio quos tempus erat iam more supervacuam cultris abrumpere carnem? (“But for those whose most holy ears are perhaps offended by the obscenity of this poet, what better or more effective remedy can I offer them than this line of the poet’s (Satires 14.44-45)...: But what are they waiting for? It is time to cut off the unnecessary flesh in the Phrygian manner”).

Finally, Lubinus again highlights Juvenal’s ethical character (crebra salutaria Sapientiae, “frequent salutary wisdom”) and his eloquence , invoking imagery of the Greco-Roman commonplace of honey (mera mella spirantia praecepta (“precepts that exude pure honey”)3

The Apologeticus from a Modern Perspective

Particularly striking is Lubinus’ pessimism towards his own time in the introductory part of the Apologeticus. At first glance, one might dismiss this attitude as the piety, not to say detachment, of the ivory tower: on the contrary, this exaggerated pessimism is precisely the most important starting point of his argumentative strategy. As a pessimist, Lubinus shares both Juvenal's unyielding anger towards his contemporaries and, albeit only implicitly, his nostalgia for an idealized past where the venerable virtues of the earliest Romans prevailed (Romani, qui [...] olim durissimi et fortissimi pastores erant [“Romans who [...] were once the hardiest and bravest shepherds”]). These vague, unwritten down moral principles allow him to inscribe a Christian ethic into the Satires. Whether this extreme pessimism is a reflection of the true conditions of his time or rather an attempt to cater to the taste of the times remains to be seen4.

Lubinus’ equation of the Satires and Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics is, however, by far the most important evidence of his moralizing approach. Although Juvenal may well be considered an advocate of ancient Roman moral principles, these principles are not systematically elaborated in the Satires. Considered solely from the author’s perspective, this could have several reasons: either Juvenal did not understand himself as a moralist (which is rather unlikely), or it is due to the fact that Juvenal, according to his own statement, was extremely inexperienced in matters of philosophy5:

qui nec Cynicos nec Stoica dogmata legit

a Cynicis tunica distantia,

non Epicurum suspicit.who has read neither the Cynics nor Stoic dogmas, differing from the Cynics only by a tunic, nor does he look up to Epicurus.

When Juvenal mentions philosophers, they often appear only as superficial symbols. Moreover, he handles their doctrines rather casually, often misquoting them. Nevertheless, Juvenal seems at first glance to show a certain closeness to Stoicism. In the Apologeticus and commentary, attempts are made in various ways to attribute a closeness to Stoicism to Juvenal. Indeed, in the second Satire, several references in the area of vocabulary to Seneca can be observed, although this is hardly conclusive proof of a Stoic inclination. If anything, Juvenal’s general tenor towards life, virtue, and vice run counter to the first principles of Stoicism. As such, the impossibly high standard that Lubinus claims for Juvenal and the boots-on-the-ground reality of Roman life simply diverge too far for a comparison to be anything but moralizing and tendentious6.

Juvenal is above all a cynical social critic and apparently has no interest in counteracting through his own actions the moral corruption depicted in his Satires. This is also shown by the moral ambiguity of his person. The praeceptor must live according to his own precepts to be considered a praeceptor. On the same subject, Juvenal expresses that he adheres to this connection between morally good character and license to criticize (Satire 1.84): loripedem rectus derideat, Aethiopem albus (“let the straight man mock the bow-legged, the white man the Ethiopian”). It is, however, quite questionable whether Juvenal’s life meets these criteria that he himself sets forth; for example, for a poet so committed to the bygone world of Roman greatness, no words of praise for Rome are to be found in the Satires. Despite (or, so the question must be asked, precisely because of?) its moral depravity, Juvenal remains there and praises in the following Satire his friend Umbricius who has decided to turn his back on the city7. In an epigram by Martial, Juvenal even wanders through one of the most infamous areas of Rome, whereas Martial presents a virtuous self-staging: he retreats as a rusticus to Celtiberis [...] terris (Celtiberian lands) (Dum tu forsitan inquietus erras/ Clamosa, Iuvenalis, in Subura,/ Aut collem dominae teris Dianae;/ Dum per limina te potentiorum/ Sudatrix toga ventilat vagumque/ Maior Caelius et minor fatigant: [...] Hic pigri colimus labore dulci/ Boterdum Plateamque - Celtiberis/ Haec sunt nomina crassiora terris [“While you, Juvenal, perhaps restlessly wander in the noisy Subura, or wear down the hill of mistress Diana; while your sweaty toga fans you at the thresholds of the powerful and the greater and lesser Caelian tire you out: [...] Here we lazily cultivate with sweet labor Boterdum and Platea - these are the cruder names in Celtiberian lands”]).

Commentary on the Second Satire

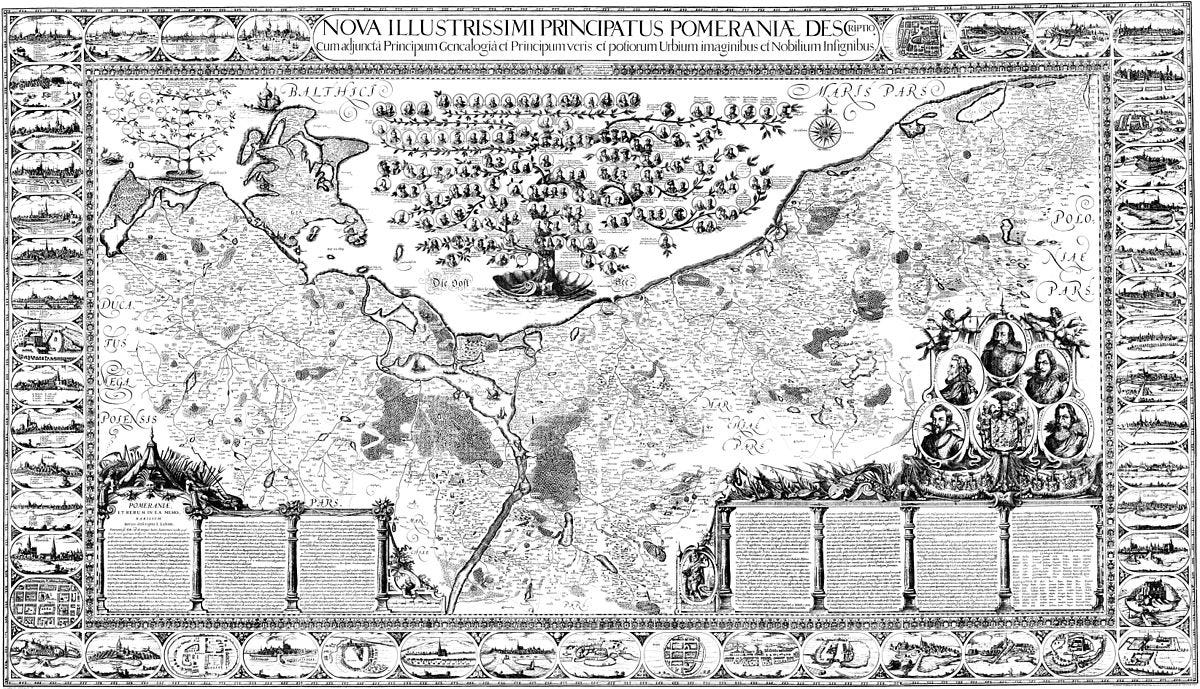

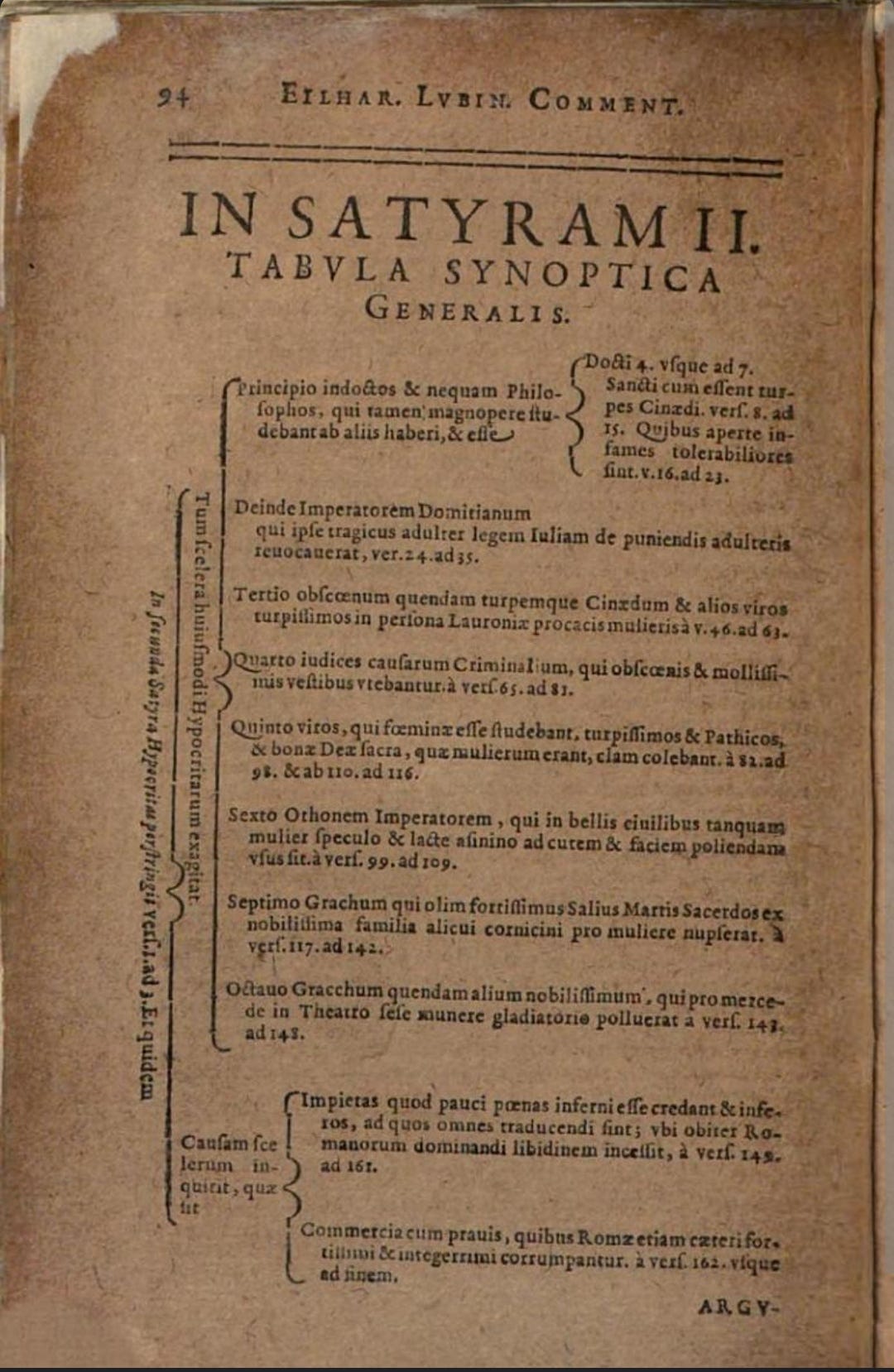

Lubinus has secured his place in posterity primarily with his map of the Duchy of Pomerania (Amsterdam 1618). This talent for the visual is already evident in his commentary in the form of tabulae synopticae (synoptic tables), which stand before the argumenta, wherein the bullet-pointed tabula is elaborated in detail. Lubinus’ understanding of Juvenal as auctor ethicus (ethical author) is clearly recognizable in both the tabula and argumentum.

Tabula Synoptica generalis

1-23 : 1. Principio indoctos et nequam Philosophos, qui tamen magnoperer studebant ab aliis haberi, et esse

4-7: Docti [...] Sancti cum essent turpes Cinædi.

8-15: † … †

16-23: Quibus aperte infames tolerabiliores sint

24-35 2. Deinde Imperatorem Domitianum qui pise tragicus adulter legem Iuliam de puniendis adulteris revocaverat

46-63:3. Obscœum quendam turpemque Cinædum et alios viros turpissimos in persona Lauroniæ procacis mulieris

65-81: 4. Quarto iudices causarum Criminalium, qui obscœnis et mollissimis vestibus utebantur.

82-93; 110-16: 5. Quonti viros, qui fœminæ esse studebant, turpissimos et Pathico, et bonæ Deæ sacra, quæ mulierum erant, clam colebant. Sexto Othono imperatorem, qui in bellis civilibus tanquam mulier speculo et lacte asinino ad cutem et faciem poliendam usus sit. Septimo Gracchum qui olim fortissimus Salius Martis Sacerdos ex nobilissima familia alicui cornicini pro muliere nupserat. Octavo Gracchum quendam alium nobilissimum, qui pro mercrede in Theatro sese munere gladiatore pollverat Impietas quod pauci pœnas inferni esse credebant et inferos, ad quos omnes traducendi sint; ubi obiter Romanorum dominandi libidinem incessit. Commercia cum pravis, quibus Romæ etiam cæreti fortissimi et integrrissimi corrumpantur.General Synoptic Table

1-23: 1. First, there are the uneducated and wicked philosophers who, despite their lack of learning, were greatly eager to be regarded as educated by others, and were believed to be so.

4-7: The learned saints, though being scandalous, were still considered tolerable.

8-15: †…†

16-23: Those who were openly infamous are seen as more tolerable.

24-35 2. Then there is Emperor Domitian, who, as a tragic adulterer, had repealed the Julian law concerning the punishment of adulterers.

46-63: 3. An obscene and disgraceful effeminate person and other very vile men, in the guise of a shameless woman from Lauronia.

65-81: 4. Fourth, the judges of criminal cases who used obscene and very soft clothing.

82-93; 110-16: 5. Fifth, men who aspired to be women, the most disgraceful and effeminate, and who secretly worshipped the sacred rites of the goddess that were intended for women. Emperor Otho, who during the civil wars used a mirror and donkey’s milk for polishing his skin and face as a woman would. Sextus Gracchus, who was once a most valiant Salian priest of Mars from a noble family, had married someone of lowly status in exchange for money. Seventh, another very noble Gracchus, who had defiled himself as a gladiator in the theater for monetary gain. Eighth The impiety of those who believed that few were punished in hell and in the underworld, to which all were destined. This led to a criticism of Roman dominion and its craving. Interactions with the depraved, by which even the most strong and upright Romans in Rome could be corrupted.

The vitium (vice) which Juvenal attacks according to his poetic program is, according to Lubinus, hypocrisis (hypocrisy) (in II. Hyprocritas perstringit; In hac Satyra [...] in Philosophos hypocritas invehitur [“In this Satire [...] he inveighs against hypocritical Philosophers”]). His attempt to give order to the rather carelessly presented content is structured in such a way that the satire is divided according to groups of people and the associated form of vitium. In the commentary, the actual theme of the satire, namely homosexuality and sexual deviance in public, appears only in the background. This has three consequences for his interpretation: firstly, the likely intended structure and thus the function of the satire is disregarded or interpreted in a moralizing-psychological way; secondly, the satirical element of the satire is thereby neglected; thirdly, to support this approach, Juvenal is presented as a Stoic (or at least as close to Stoicism).

Preliminary Remarks: Lubinus’ Stylistic Peculiarities

There are some stylistic features that are typical of Lubinus: 1) pathetic exclamations and paraphrasing, not infrequently in the present tense, in all probability in imitation of Juvenal’s style, which are intended not only to clarify the content but also seem, from Lubinus’ perspective, to be transferable to his own time (Cf. O deum immortalem! [...] in vita et in moribus? [“O immortal god! [...] in life and in morals?”]; Tu o Mars [...] tua terram pulsas [“You, O Mars [...] who strikes your earth”]); 2) numerous, often keyword-like explanations in German, which are aimed at his intended audience, i.e. young students.

Hypocrisis and Punishment in Lieu of of Effeminacy and Homosexuality

Lubinus deals with the sensitive topic of the second satire in different ways. It is pushed into the background when it seems more plausible to cite the leitmotif of the vitium hypocrisis; when it is clearly about pathici (passive homosexuals), the historical context, i.e. Roman understanding of homosexuality that allows such behavior, is omitted and replaced by Lubinus’ moral doctrine ad usum Delphini. Next, he draws attention to Lucian's text πρὸς τὸν ἀπαίδευτον καὶ πολλὰ βιβλία ἐωνημένον (Against the Ignorant Book Collector) in order to polemicize against his own time through Juvenal (see Late patet etiam hoc saeculo vana illa superstitio dicam, an persuasio [This “vain superstition, shall I say, or persuasion, is also widespread in this century”])8. It therefore seems unlikely that Lubinus was unaware of the fact that the anti-hero of this work, like those of the second Satire, was also a vir pathicus (passive homosexual man). There is no doubt that in the brief first part of the satire (which comprises only a fifth of the entire satire), the impudence of hypocritical moralists is addressed, but the far more important theme of the satire, already alluded to by the reference to Lucian, is pushed into the background in favor of his moralizing program. That is, through psychologizing the action, the vitium is elevated to a peccatum (sin). He paraphrases a passage from Lucian, which in itself is only marginally significant for the structure of the satire, but serves his purpose of equating Juvenal's time with his own:

Et nostra, inquit, aetate fuit qua, et adhuc superest opinor Stoici Epictati sictilam Lacernam ter mille drachmis emit: sperabat enim opinor. Et ille si noctu ad illam lacernam tegeret, continuo et Epicteti sapentiam [...] se adepturum et similem se fore admirandi illius senis.

And in our age, he says, there was and I believe there still remains [someone who] bought the earthenware lamp of the Stoic Epictetus for three thousand drachmas: for he hoped, I believe, that if he read by that lamp at night, he would immediately acquire the wisdom of Epictetus [...] and become similar to that admirable old man.

Homosexuality, insofar as it is explicitly mentioned, is continually referred to as scelus (crime) and condemned by Lubinus as unnatural; the lex Scantinia is explained as a general prohibition of homosexuality. However, Juvenal, like most Roman citizens of his time, is not against homosexuality per se (and certainly would not have considered it an unnatural drive), but against viri pathici, who through their passive sexual behavior renounce their masculinity and thus their right to Roman citizenship. In passages where the thematic complex of homosexuality and effeminacy comes to the fore (effoeminatos, qui agunt vicissim et patiuntur, i.e. “effeminate men, who act and are acted upon in turn”), Lubinus offers explanations with a strongly moralizing flavor, the usefulness of which is sometimes difficult to justify considering the context.

The men in v. 54-7 tract[ant] contra muliebria officia (“perform in place of womanly duties”). They are ashamed of their naturally given masculinity and make themselves into women: their existence is primarily an affront against nature itself, not against tradition or laws. The concluding part of this comparison, where the same men are equated with a pellex (“concubine”), is explained by a scholiast: magno odio habetur apud uxorem ea, qual domino miscetur. ergo hanc insequens gravioribus poenis domina catena vinctam infinit codici atque ita iubet facere pensa (“she who mingles with the master is held in great hatred by the wife. Therefore, the mistress, pursuing her with heavier punishments, binds her chained to the stocks and thus orders her to do her tasks”). Lubinus adopts this explanation and provides two examples (Plaut. Poen. 1153, Prop. 4.7.44), which also mainly deal with the portrayal of punishment.

However, the comparison primarily serves, as Lubinus himself writes, to portray the men as effeminate9: as the comparison reaches its climax, it is precisely the instrument of punishment (codex) that is actualized through its contemporary equivalent (apud nos catastae roboreae, die dulle Kaste [among us wooden stocks, the “dull box”]), to which furiosi (madmen) were bound: a much more vivid image for Lubinus' audience than his explanation of the meaning of the passage, which seems more like a cursory interim remark.

The weight of the satire is placed entirely on crime and punishment in the last section, a κατάβασις (descent) (esse aliquos [there are some]), in which the pleasures of Rome’s citizens are scorned and their noble ancestors are praised in a catalog of heroes. More generally, it focuses on the inevitability of moral responsibility. As Lubinus puts it: impietas quod pauci pœnas inferni esse credebant et inferos, ad quos omnes traducendi sint; ubi obiter Romanorum dominandi libidinem incessit (“impiety because few believed in the punishments of hell and the underworld, to which all must be led; where he incidentally attacks the Romans’ lust for domination”).

First, a series of viri integrissimi (most upright men) is contrasted with the depraved men of his time: if such “shadows” (monstrosus et prodigiosus peccator cuius adventu sanctae illae animae etiam inficerentur [“monstrous and prodigious sinner by whose arrival those holy souls would even be infected”]) reached them, they would have to purify themselves. Moreover, he can draw a general moral lesson from these verses: whether we believe it or not (omnium animis inferiorem metus, sublatus est, etiam puerorum, nisi admodum infantes sint [“the fear of the underworld has been removed from the minds of all, even of children, unless they are very young”]), night will enclose us and we will appear before the iudices infernales (“infernal judges”) to render account of our lives and deeds.

In fact, the concluding part does not so much function as a reminder of our moral responsibility as mortals, but as a final attack on the effeminate men, this time from the fictional perspective of established figures of Roman masculinity. The pompous-satirical tone of a didactic poem, which is struck with esse aliquos [...] et (there are some [...] and), as well as the rationalizing argument at v. 151, which make the κατάβασις “appear in a ridiculous light,” are not mentioned; the external vices, i.e., the crimes against gravitas (dignity), with which Juvenal deals, are psychologized and stylized into moral precepts. This omission of explicitly satirical elements will be discussed in more detail at a later point.

The Figure of Laronia

This also somewhat mitigates the moral ambiguity of Laronia, who criticizes Hispo and Hister in her speech. Initially, Lubin seems to concede that Laronia is a matrona nobilis (“noble matron”), but later writes that she is, in fact, quaedam meretrix (“a certain courtesan”) who assigns her own vices to men, which, at first, is a remarkable and false irony, and she reproves simulatators and hypocrites.

A Question of Form: Lubinus’ Interpretation of the Structure

Lubinus’ moral program and its interpretative implications are crucial for his description of the structure of the satire, as seen in the synoptic table. For Lubinus, Hispo (v. 50) is quodam turpis cinaedus (“a certain shameful cinaedus”), a man [...] unclean, and a fellator who submits to the young men, and inclines to endure being sodomized. Lubin primarily uses Hispo's appearance to briefly cover the obscene sexual vocabulary of Juvenal (foedissima aliquot vocabula); Hister (v. 58) is subsumed under the same type: a wealthy person but a pathicus, who defiles the tablets of his own free will [...] for the freedman Draucus was. Creticus is an iudex (“judge”)...who used soft garments, although he is also described as acerbus (“harsh”) and of noble origin. Those who, against custom, worship the Bona Dea are men who wished to be women; Gracchus, once a priest of Mars, has also become a pathicus. The appearance of the other Gracchus as a gladiator (v. 143) is even worse than the homosexual marriage, for he, like some nobles of Juvenal’s time, has voluntarily forfeited his noble origin (v. 121) and dares to rear his head in the most public of arenas10. The moralizing interpretation is clear; all have morally “deteriorated,” still holding important offices (or being of high rank) and thus making themselves hypocrites. The main theme, somewhat evident, is the implied homosexuality due to effeminacy, though, as shown earlier, it is pushed into the background. The most important aspect of the main theme that significantly shapes the structure of the satire is, as Lubinus omitted in favor of his moral-educational interpretation, the aspect of publicity. Thus Schmitz: “The gradual development from initially hidden and merely domestically practiced vice to public exposure forms the actual theme of the 2nd Satire [...] The representation is clearly designed as a crescendo, a structure that aligns with the intention of the satirical poet to trace the gradual development from hidden vices to public shame.” This is repeatedly suggested by Juvenal’s vocabulary and the numerous references from the scholia. The cognomen Hispo was deliberately used to emphasize the noble rank of the fictional criminal. Thus Syme: “The cognomen 'Hispo' is uncommon, apparently attested only for Cicero's friend the publicanus P. Terentius Hispo [...] for a magistrate at Caelium in Lucania, and for the Trajanic senator M. Eppuleius Proculus Ti. Caepio Hispo.” Similarly, the tension between private and public with Hister and his draucus is highlighted: “The rare Latin word draucus is known almost exclusively from Martial. Older dictionaries and handbooks used to gloss the word as 'sodomite' [as Lubinus did], until Housman showed that draucus is in fact 'as innocent a word as comoedus, and simply means one who performs feats of strength in public'." The role of publicity, historicity, and satirical function of the Bona Dea and Gracchus episodes will be discussed in more detail in the next section. Considering this, the following schema of the main figures mentioned in the main part emerges:

1. Hispo (private, noble; probably invented);

2. Pacuvius Hister (quasi-private, plebeian, tries to hide his secret from the public; real);

3. Creticus (public, real, probably also a Stoic);

4. Defilement of the Bona Dea rites (private; crime against the state; exaggerated-satirical); Marriage of kinādes (public, crime against the state; exaggerated-satirical); 5. Appearance of Gracchus as a gladiator (public, disgrace against the state and tradition; exaggerated-satirical).

By omitting this aspect, which would only be depicted through the drastic changes of scenes, from the home of Hispo and Hister to the arena of Gracchus, it is evident that Lubinus is content to regard the satire as a rhetorical tool for Christian moral teachings, without taking Juvenal’s ethical views into account (especially his esteem for gravitas), even though they are only vaguely and briefly outlined.

A Question of Style: A Satire Without Satirical Exaggeration

Exaggeration is considered a feature of the satirical genre and is part of every satirist’s stylistic repertoire. The sharp cruelty with which Juvenal attacks his enemies gives him a special position among satirists, both on a moral-educational and linguistic level, as even Lubin claims. Thus Schmitz: “Frequently, linguistic signals indicate that Juvenal has exaggerated the conditions to such an extent that the listener or reader must question whether he should take the depiction literally [...] A once mythical or historical event is elevated to the status of a habitual occurrence.” The defilement of the Bona Dea rites (v. 83-90) and the marriage of kinādes (v. 117-120) are exemplary of the exaggerated generalization found in satire. Although Lubin acknowledges a certain degree of exaggeration as a feature of the genre, he presents these two events as fundamentally historical facts or historical figures. After a brief history of the origin of the cult, he writes about those who, imitating women, performed clandestine rites to worship Bona Dea. A Greek counterpart (even with a relevant reference in a comedy by Eupolis) of the cult also exists: “There was, however, a book titled Baptae, which Eupolis wrote about the Athenians who, imitating women, disturbed the Corytto psalmist [...] There was Cotytto, a goddess of women among the Athenians, as among the Romans there was the goddess Bona.” Such a cult is, however, not historically verifiable; the episode was probably written in reference to the well-known Clodius scandal of 62 BC (Cic. Har. Resp. 37; Plut. Caesar 9). The same applies to the marriage of Gracchus: “For one of them [i.e., among the Gracchi], a man like a woman, married a man named Cornicinus; and the other [...] defiled himself with gladiatorial duties." And later: "He attacks Gracchus himself, [...] who once was a martial priest of Mars, now marries a man instead of a woman.” In fact, Gracchus was a historical figure, but not the one mentioned in the satire. Like the previous episode, this is taken from a historical event: “The marriage is likely that of Nero with Sporus and Pythagoras.” Moreover, the last section of the satire, vv. 159-160, is understood as a harsh critique of Roman pride: “He condemns the desire for empire [...] What good is it to conquer men, when we become slaves of our vices?" In fact, a similar interpretation is found in the old and new scholia, which Lubinus most likely adopted, but as Courtney has shown, this claim can be partly refuted, as the last two episodes are based on a historical event and also have a satirical function. In conclusion, Lubinus only partially looks to historical sources to verify the truth of the events depicted in the satire; as long as these occurrences can be used purposefully, their historicity is readily accepted, and their function as satirical exaggerations is simply ignored11.

Juvenal as a Stoic

Lubinus does not tire of granting the Stoics an unequivocally positive special status: a status that is not found in the satire but rather seen as a trace of his philosophical attitude. This commendation of Stoicism, which is also subtly attributed to Juvenal throughout the commentary (understandably with parallels to Seneca’s letters), ignores the fact that Juvenal most likely did not read these philosophers and was therefore unable to appreciate or take them as models. Concerning the Stoic Chrysippus, whose plaster likeness is described as highly desired among the indocti, Lubinus writes an almost encomiastic explanation: fuit ille Zenonis et Cleanthis auditor ingeniosus et tantus Dialecticus ut dicerent, si apud Deos usus esset Dialectiae, non fore nisi Chrysippeam [...] Fuit multi Labors et post se reliquit 75 Volumina (“He was a student of Zeno and Cleanthes and such a dialectician that it was said, if there was a use of dialectic among the gods, it would be nothing but Chrysippean [...] He was of great labor and left behind volumes”). In the old scholia, it simply says: qui fuit Stoicorum princeps (“He was the chief of the Stoics") — in fact, only in the newer scholia does this ‘Lubinite’ tendency appear: philosophus fuit nobilissimus (“He was the noblest philosopher”). It is thus clear that Lubinus has a decidedly positive attitude toward the progressive humanist figure Socrates (like Juvenal a praeceptor morum) and his successors. Thus, Lubinus comments on v. 9-10: Inter Socraticos cinaedos: inter illos qui more Socratis de virtute et honestate severissime disputant, interim cinaedi et Pathici muliebra patiuntur (“‘Among the Socratic scholars’: among those who, like Socrates, discuss virtue and honor with the utmost severity, there are sometimes effeminate men and ‘pathics’ — in modern parlance, "“faggots” — who endure feminine behaviors”)12

The κλέος (glory) of Socrates emerges unscathed from the criticism: Juvenal might be aiming to polemicize against some of Socrates’ successors who deviate from Socratic severitas by tolerating “soft” individuals. This notion, however, does not align with Juvenal's general attitude towards the Stoics nor with the scholia with which Lubinus was obviously conversant.

Some conclusions …

Lubinus’ incorporation of Christian ethics reveals a psychological approach to external vices, such as breaches of gravitas, which Juvenal condemns. He justifies this by, among other things, omitting historical facts regarding homosexuality. As we have seen, for Lubinus, even the Otho episode serves as an example of how Juvenal criticizes hypocrisy, although it pertains solely to external appearances and the behavior of a worthy man in war. While Lubinus’ attempt to address Juvenal’s obscenity clearly distinguishes his commentary from earlier ones, which often tend toward suppression or bowdlerization of the text, his moralizing agenda partially connects his commentary to the same tradition he seeks to distance himself from.

O century, O sciences ... O century, O learning, it is a pleasure to be alive, though not yet to retire, Willibald. Studies are flourishing, minds are stirring! You, Barbarism, take the noose and prepare yourself for exile!

Thomas Naogeorgi Satyrarum, liber I, v. 6-11.

For comparison, read Pausanias 9, 23,2; 16,305 and Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura Book 1, 936-950.

Lubinus’ overall grumpiness likely stems from a dispute over his theological treatise Phosphorus sive de prima causa et natura mali, published in Rostock in 1596, in which he was accused of Manichaean dualism. His work was criticized for its perceived alignment with Calvinism and Platonism, with opponents advocating for Aristotelianism as a philosophy more harmonious with Christianity. One might also draw a parallel between the contrasting perspectives of Juvenal and Pliny, and those of Hutten or Naogeorgus and Lubinus. Juvenal’s grim depiction of Roman society stands in stark contrast to the more optimistic view presented by his contemporary, Pliny the Younger. This raises the question: Did Pliny live in an artificially insulated world, or was Juvenal's portrayal of society deliberately exaggerated and misleading? I leave the reader to draw their own conclusions.

This view has been most pointedly expressed in modern scholarship by J. D. S. Green in Juvenal and Persius: A Study in Satire (p. 122): “As we look over these names and the passages in which they, i.e. philosophers, occur, we see clearly that Juvenal knows scarcely anything about them. Aristotle, Chrysippus, and Cleanthes appear only as busts in the homes of poseurs; and so does the remote Pittacus, who is so far from being a real philosopher that Juvenal evidently took him, as he took Thales, from a list of the seven sages [...] The conclusion is clear. The leading Greek philosophers Juvenal seems to know only as shallow stereotypes. They are not for him the creators of so many vast systems of thought; they are quaint and eccentric personages who lived in tubs or at times not even that, but merely plaster busts on a shelf. In this his poems are a striking contrast to the satires and letters of Horace and Persius, both of whom knew a good deal of philosophy and had vital and original ideas about the subject.“

Also Green (p. 161): “Yet his knowledge of Stoicism is limited, as his mistake about cannibalism shows. And when we look at his use of Stoic doctrines we find that he seldom or never adopts them whole-heartedly and usually alters them freely [...] For example, Seneca writes that one serious cause of anger is the spectacle of prosperous vice and successful crime which can be seen in the streets of Rome (De ira 2.7-9). So does Juvenal (1.22- 80). But Juvenal draws one conclusion, that he must write angry satire; while Seneca draws the other and opposite conclusion, that the wise man must restrain his anger at this sight.” Gilbert Highet is even more strident in his The Classical Tradition: Greek and Roman Influences on Western Literature (p. 224): “But his character was not really sympathetic to Stoicism either. He is too passionate. He protests too much, far too much. He is too anxious. He is too angry, too scornful. He hopes too much, and therefore despairs too much. In fact, he is too unhappy; and the perfect or progressing Stoic was not unhappy. He has little or none of the Stoic sense of duty, and never conceives that he has any obligation to serve the human community.”

Tom Geue has rather humorously characterized Juvenal’s third Satire as a “privileged piece of verbal diarrhea.” The essay to read is The Loser Leaves (Rome's Loss): Umbricius's Wishful Exile in Juvenal's 'Satire' 3.

One may compare this to Lubinus’ complaint about “books without scholars”: Accidit in Germania nostro tempore: ut Doctor quidam iuris, ex hac familia oriundus, et in horum Philosophorum ludo edoctus, indoctus, et ignavus, multos itidem et egregios libros, et amplissimam bibliothecam possideret. Ille cum forte ex negotio alium Doctorem iuris, virum doctum, et vere literarum inviseret, eiusque Musaeum non ambitiose egregiis picturiis et multa librorum copia ornatum videret, superbe ipsum (ut numquam non indocti) compellavit: Salve Doctor sine libris [...] libri sine Doctore (“It happened in our time in Germany that a certain doctor of law, originally from this family and educated in the school of these philosophers, though unlearned and lazy, possessed many distinguished books and an extensive library. One day, while on business, he visited another doctor of law, a learned man, and genuinely erudite, and saw his museum adorned with excellent paintings and a great abundance of books, not ostentatiously but with great elegance. The former, being typically unlearned, addressed him arrogantly: "Greetings, Doctor without books [...] books without a Doctor”). Some things never change — surely we all know at least one person who fits this description.

This seems to be the most likely interpretation in light of the context, however it is not without its textual problems, as Edward Courtney has suggested in A Commentary on the Satires of Juvenal (p. 103): “But the point of the line is obscure [...] the wording does not suggest, as the context demands, delicate work, and seems rather to lessen than to emphasise the effeminacy of the men. Moreover with STAMEN as the antecedent of QUALE, 57 would more naturally precede 56. Perhaps a line has been lost after 56 which said that the men produce fine work, not rough spinning like that of the paelex.”

Recent research has demonstrated that “the Bride” Gracchus and the Gladiator Gracchus are the same person. By splitting Gracchus into two—each described according to the appearance of their vice—Lubin's moralizing approach becomes evident. If the same Gracchus is meant in both cases, the theme of public visibility is highlighted, i.e., that Gracchus's appearance as a gladiator after his marriage is considered worse than the marriage itself, especially since it occurs openly.

Linguistic elements of satirical exaggeration and double entendre are also omitted. For instance, cornici (to the crow) serves as a metaphor, suggesting, as Probus notes, that the subject possesses a characteristic akin to having a large horn. Similarly, Lubinus refers to the notion that the entire flock corrupts the fold. The scholia, in contrast, mention: uva uvam videndo varia fit (grapes change color by seeing grapes), and compare it with βότρυς πρὸς βότρυν πεπαίνεται. However, this line is considered spurious.

Unlike the scholion, which traces the Latin cinaedus to κύων (dog), Lubinus, in spite of his moralizing bluster, comes closer to the actual etymology: namely, a compound of κύνειν (to move) and αἰδοῖα (genitals).